Matthew’s dependence on Luke: Matthean Posteriority

This article presents evidence for the author of Matthew having used Luke in the composition of the Gospel of Matthew. The view of Matthew being the last of the three Synoptic gospels and having a dependency on Luke is known as Matthean Posteriority. Posteriority is the state of being later or subsequent. In addition to the Jerusalem School, this view has been advocated by numerous bible scholars over the last few hundred years. Other NT scholars have recognized the merits of Matthean Posteriority. An example is David A. deSilva’s, in his An Introduction to the New Testament:

Martin Hengel has drawn attention to the fact that, while Luke’s use of Matthew remains problematic in the extreme, the possibility that Matthew has used Mark and Luke has not been given adequate attention and may prove, in the end, the most elegant solution… Matthew’s systematization and rearrangement of Luke’s material would certainly be easier to explain than the reverse. (David A. deSilva, An Introduction to the New Testament: Contexts, Methods and Ministry Formation (Downers Grove, IL: interVarsity, 2004, p. 165)

Matthew Expands upon Luke

In his book ‘The Myth of the Lost Gospel, Evan Powell extensively documents how Matthean passages incorporate revisions of Luke. In his analysis, Powell identifies seven categories of tradition that shows Matthew is much more expansionist as compared to Luke. Although Luke is 107% as long as Matthew, in all seven categories of tradition, Matthew contains the highest concentration of material. The result as reported on page 41 are not coincidental:

- Supernatural Events: Luke has 77% as many references as those in Matthew

- Eschatological content: Luke has 71% as much as Matthew

- Ethical sayings: Luke has 73% as many references as those in Matthew

- Jesus as Christ: Luke has 75% as many references as those in Matthew

- Jesus as Son of man: Luke has 83% as many references as those in Matthew

- Kingdom of God: Luke has 75% as many references as those in Matthew

- God as Father: Luke has 36% as many references as those in Matthew

Powell sums up these results as follows:

We find that the community that produced Matthew developed a more refined and expansive interpretation of Jesus’ traditions across the entire spectrum of thought. Not only are the Lord’s Prayer and the Beatitudes and the Great Commission presented in more evolved form in Matthew, but the content of Jesus’ ethical message is richer, the visions of the end-time events are more extreme, supernatural mythology is more diverse, and the concept of the intimate fatherhood of God is more developed. Collectively, Matthew contains an enrichment of all prominent aspects of the Jesus story, surpassing the material found in Luke, while Luke contains virtual subsets of the material found in Matthew.

Therefore, Matthew presents a more mature expression of the Church’s interpretation of Jesus. The statistical distribution of materials between Luke and Matthew, as well as the qualitative enhancements of Matthew over Luke, are consistent with the proposition that Matthew was composed some time after Luke. Moreover, there was an interval of time between the two that would allow for all facets of the Jesus tradition to have evolved into the more sophisticated form that are documented in the Gospel of Matthew…

[Some] theories argue that Luke was dependent on Matthew. Yet, the date we have just reviewed is difficult to explain under such a scenario. We must imagine that Luke, in using Matthew as a source, managed to diminish its traditions across the board both qualitatively and quantitatively, while at the same time producing a Gospel that was longer than Matthew by 7%. In the process he eviscerated the Lord’s prayer and the Beatitudes; he dismantled the Sermon on the Mount and reformulated it as a more anemic Sermon on the Plain; he diminished the ethical vision of Jesus; he removed most of Matthew’s references to the intimate fatherhood of God; and finally, he eliminated the decisive command from Matthew’s Great Commission to “go therefore and baptize all nations in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit,” and replaced it with a statement that repentance and forgiveness should be preached to all nations, but that the disciples should wait in the city until further notice.

It is difficult to imagine what Luke would have had in mind to have used Matthew in this manner. Yet, as we shall ultimately discover, these are just the first of many editorial eccentricities of which Luke would be guilty were he to have used Matthew as a source.

(Evan Powell, The Myth of the Lost Gospel (2006), pp. 42-43

A few more examples of Matthean revision to Luke

These revisions are clarifications or embellishments which are most obvious. The clarifications are in areas where Luke embodies a difficult reading. Evan Powell, in his book The Myth of the Lost Gospel, devotes much of his book to showing how Matthew attempts to provide clarification in areas where Luke and Mark might be ambiguous. Powell states in the opening paragraph of the third chapter:

One of the curious features of the Gospels of Mark and Luke is that they contain stories which, if left on their own without explanation, had the potential to create theological confusion or historical skepticism. These may be viewed as the “loose ends” of the traditions. An editorial objective of Matthew was to tie up these loose ends by resolving tensions which were left standing in the earlier Gospels, and providing new solutions to puzzling questions. The existence of this unique explanatory material in Matthew constitutes more evidence that Matthew was the last of the Synoptic Gospels to have been composed. (Evan Powell, The Myth of the Lost Gospel (2006), p. 69)

The embellishments of Matthew are verses revised to make the text more exaggerated. There are many examples of this as well. Notable changes are highlighted in bold.

Luke 17:3-4 (ESV), “seven times”

3 Pay attention to yourselves! If your brother sins, rebuke him, and if he repents, forgive him, 4 and if he sins against you seven times in the day, and turns to you seven times, saying, ‘I repent,’ you must forgive him.”

Matthew 18:21-22 (ESV), embellishment to “seventy-seven”

21 Then Peter came up and said to him, “Lord, how often will my brother sin against me, and I forgive him? As many as seven times?” 22 Jesus said to him, “I do not say to you seven times, but seventy-seven times.

The embellishment of Matthew 18:22 makes a more compelling portrait of Jesus.

Luke 14:26-27 (ESV), “hate”

26 “If anyone comes to me and does not hate his own father and mother and wife and children and brothers and sisters, yes, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple. 27 Whoever does not bear his own cross and come after me cannot be my disciple.

Matthew 10:37-38 (ESV), Revision

37 Whoever loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me, and whoever loves son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me. 38 And whoever does not take his cross and follow me is not worthy of me.

Matthew 10:37-38 is a revision of Luke 14:26-27 that eliminates the more difficult word “hate” for making a positive rendition that focuses upon impulses toward love and allegiance. The later Matthean text is in keeping with Jesus being calm. The reworking of the saying softens it and makes it more palatable for the church. Matthew also softens the context from being a disciple to being unworthy. It can be argued that we are unworthy, but that doesn’t disqualify us from being Jesus’ disciples. Matthew eliminates reference to wife, brothers, and sisters because people tend to have the closest bond with, father, mother, son, and daughter. These added relations are not necessary to illustrate the point. Matthew essentially is a revisionist commentary on Luke, which attempts to resolve the difficulty in interpreting the text of Luke by rewording it in a clarifying way.

Luke 3:7-8 (ESV), “crowds” + “begin”

7 He said therefore to the crowds that came out to be baptized by him, “You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come? 8 Bear fruits in keeping with repentance. And do not begin to say to yourselves, We have Abraham as our father.’ For I tell you, God is able from these stones to raise up children for Abraham.

Matthew 3:7-9 (ESV) “Pharisees and Sadducees” + “presume”

7 But when he saw many of the Pharisees and Sadducees coming to his baptism, he said to them, “You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come? 8 Bear fruit in keeping with repentance. 9 And do not presume to say to yourselves, We have Abraham as our father,’ for I tell you, God is able from these stones to raise up children for Abraham.

Matthew revises the text to direct the rebuke to the religious elite, not the multitudes at large. The revisionist apparently felt the rage of the Baptist was more appropriately directed at the Pharisees and Sadducees.

Further evidence of Matthew Editing Luke is substituting “begin” with “presume.” The reason this is so significant is that Matthew does this all over the place in terms of editing out “begin” from Mark five times. See Mark 5:17 vs. Matt 8:34, Mark 10:28 vs. Matt 19:27, Mark 10:41 vs. Matt 20:24, Mark 13:5 vs. Matt 24:4, and Mark 14:19 vs. Matt 26:22. The author of Matthew apparently doesn’t like what are various uses of the verb to begin, as the author routinely eliminates them (or places them in more precise context as he transcribes Mark). It is not reasonable to infer that Matthew has performed the same edition of Luke in Luke 3:8 vs. Matt 3:9.

Luke 23:50-53 (ESV) (also Mark 15:43)

50 Now there was a man named Joseph, from the Jewish town of Arimathea. He was a member of the council, a good and righteous man, 51 who had not consented to their decision and action; and he was looking for the kingdom of God. 52 This man went to Pilate and asked for the body of Jesus. 53 Then he took it down and wrapped it in a linen shroud and laid him in a tomb cut in stone, where no one had ever yet been laid.

Matthew 27:57-60 (ESV)

57 When it was evening, there came a rich man from Arimathea, named Joseph, who also was a disciple of Jesus. 58 He went to Pilate and asked for the body of Jesus. Then Pilate ordered it to be given to him. 59 And Joseph took the body and wrapped it in a clean linen shroud 60 and laid it in his own new tomb, which he had cut in the rock. And he rolled a great stone to the entrance of the tomb and went away.

This change in Matthew 27:57 is similar to the previous change, in Matthew 3:7 in that the author heightens the antiparasitic polemic. First to direct John the baptists’ rage more directly toward them, and second to remove the implication that the Joseph who provided the tomb was one of them. Matthew appears to intend to amplify Jesus culpability in the death of Jesus, which is also evidenced by the interpolation of Matthew 27:24-25, which has no parallels in the other gospels. According to this aim, he would rather not have a member of the Jewish ruling council described as a good, righteous, and respected man who was looking for the kingdom of God. It is contrary to the authors’ aims to portray a member of the Sanhedrin as assuming responsibility for the honorable burial of Jesus. Matthew redacts the identity of Joseph of Arimathea that exists in Luke and Mark, and simply describes him as a “rich disciple” with no indication of being associated with the Sanhedrin. Here is another piece of evidence that Matthew was the last and most ideologically developed of the Synoptic Gospels. It would make no sense, if Matthew was the earliest tradition, for Mark and Luke to recast a disciple of Jesus as a member of the Jewish council. Thus, Luke embodies the more primitive tradition and Matthew a later revision.

Matthew’s mitigation against resurrection skepticism

According to Mark and Luke, Jesus’ body is laid in a tomb and a stone is rolled in front of it. When Mary Magdalene and others go to the tomb, they find the stone rolled back and the body of Jesus gone. To eliminate the possibility that the disciples had come at night and stolen Jesus’ body, the account was revised in Matthew 27:62-66. The account of the sealed and guarded tomb is added.

Matt 28:1-6 was added to address further complications. Since the stone was sealed, a supernatural force is incorporated to break it. Since the guards are watching, they must see the tomb actually open. They are watching as the stolen is rolled back. When this happens, according to Matthew, Jesus’ body is already gone from the tomb. However, like Luke and Mark, the women arrive at an open and empty tomb.

Matthew 28:11-15 further adds expansive material to further undermine the stolen-body theory. None of this Matthean material addressing the claims of conspiracy appears in Mark or Luke. This is a special case where, in addition to expanding upon the saying of Jesus, the author of Matthew actually expands the narrative to address later skepticism about the resurrection.

Summary of Matthews’ Revisionist Character

The following observations contribute to the conclusion that Matthew incorporates a later revision of more primitive Lukan material.

- The key traditions including the Lord’s Prayer, the Beatitudes, the Sermon on the Mount, and the Great Commission take on more evolved and expanded (Liturgical) forms in Matthew as compared to Luke

- The distribution of the material, in Matthew, suggests it was produced at a later stage of the Church’s development. The evidence indicates that Matthew used Mark as a primary source and supplemented his restructuring of Mark with reworked passages from Luke.

- Matthew exhibits numerous corrections and clarifications. This includes reinterpretations of Jesus’ character and corrections of a theological or ideological nature that does not exist in Mark. It is highly improbable that all this material would have been removed by Luke had he used Matthew as a source.

- Matthew clarifies and neutralizes controversial aspects of Luke that had apparently become flash points for debate or for skepticism.

According to Powell:

There is ample evidence to establish Matthew as the last of the Synoptics. Matthew frequently offers more sophisticated reflection, building upon materials in Mark and Luke. He also tends to alter or embellish his sources when it suits his ideological agenda… It follows that if there was, in fact, any direct literary dependence between Matthew and Luke, it would have been that of Matthew’s dependence upon Luke. Luke could not have known the Gospel of Matthew for the simple reason that it had not yet been composed. (Evan Powell, The Myth of the Lost Gospel, p. 83)

Examples of Progressive Embellishment

The Article Progressive Embellishment, Luke→Mark→Matthew presents 36 instances of progressive embellishment, comparing the stages from Luke to Mark to Matthew. The article features parallel tables, a comparative analysis, and word count data. In addition to these exemplary examples of the Progressive Embellishment article, below is a supplementary list of 36 additional parallels that showcase revision and/or expansion from Luke to Matthew, which are not found in Mark. These smaller parallels demonstrate Matthew’s tendency to offer a more refined and embellished text, exhibiting improved clarity compared to the earlier, more primitive version found in Luke.

- Luke 6:20-23 → Matthew 5:3-12

- Luke 6:27-28 → Matthew 5:43-44

- Luke 6:31 → Matthew 7:12

- Luke 6:32-33 → Matthew 5:46-47

- Luke 6:36 → Matthew 5:48

- Luke 6:43-45 → Matthew 7:15-20

- Luke 6:46 → Matthew 7:21

- Luke 6:47-49 → Matthew 7:24-27

- Luke 7:9 → Matthew 8:10-12

- Luke 9:20 → Matthew 16:16

- Luke 10:23-24 → Matthew 13:16-17

- Luke 11:2-4 → Matthew 6:9-13

- Luke 11:21-22→ Matthew 12:29

- Luke 11:30 → Matthew 12:40

- Luke 11:42 → Matthew 23:23

- Luke 11:44 → Matthew 23:27-28

- Luke 11:46 → Matthew 23:4

- Luke 11:47-48 → Matthew 23:29-32

- Luke 11:49-51 → Matthew 23:34-36

- Luke 11:52 → Matthew 23:13

- Luke 12:2-3 → Matthew 10:26-27

- Luke 12:4-7 → Matthew 10:28-31

- Luke 12:8-9 → Matthew 10:32-33

- Luke 12:24 → Matthew 6:26

- Luke 12:29-31 → Matthew 6:31-33

- Luke 12:33–34 → Matthew 6:19–21

- Luke 12:39-40 → Matthew 24:42-44

- Luke 12:51-53 → Matthew 10:34-36

- Luke 13:24 → Matthew 7:13-14

- Luke 13:25–27 → Matthew 7:22-23

- Luke 14:26 → Matthew 10:37

- Luke 16:16 → Matthew 11:12-15

- Luke 16:17 → Matthew 5:18

- Luke 17:6 → Matthew 17:20

- Luke 19:11-27 (Minas) → Matthew 25:14-30 (Talents)

- Luke 22:41-42 → Matthew 26:39

Matthean Conflation of Mark and Luke

When considering the possibility that Matthew conflated Mark and Luke Together, examining the text, it becomes obvious that the author’s objective was to rewrite the Gospel of Luke with particular narrative and theological aims. The result of this effort is a more comprehensive version of the Gospel story. Although he embraced much more of Mark than Luke, he expanded upon many of Luke’s key traditions. He refocused the Jesus story within Jewish tradition. Scholars such as Powell acknowledge that Mark is the primary source of Matthew’s narrative structure, while Luke is a secondary source that the author sometimes incorporates and integrates with material from Mark. (Evan Powell, The Myth of the Lost Gospel, p. 90)

Powell further makes the following observations regarding the procedure employed by the author of Matthew.

Though Matthew has a similar scope in the storyline as does Luke, the author was motivated to produce a thoroughly original Gospel, and one that looked as much unlike Luke as the material would allow. Matthew is often guided by a simple “not-Luke” approach—on occasions where Luke followed Mark, Matthew was not motivated to diverge; whenever Luke diverged from Mark, Matthew felt free to follow Mark more closely. In the triple tradition, Matthew never takes over significant Lukan texts against Mark. In the double tradition, when Matthew is aware of earlier forms of Lukan sayings, he substitutes the earlier forms. When he is not, he edits them or recontextualizes them, or both. When Matthew replicates Luke’s material with a high verbal agreement, he always chooses to situate it differently relative to Mark. In most cases, he scans, selects, and reassembles Lukan sayings into radically different narrative contexts. Matthew rejects Luke’s infancy and genealogy texts, and replaces them with mythologies that are consistent with his own theological agenda. He discards Luke’s resurrection narrative and replaces it with a fulfillment of the Markan foreshadowing that Jesus would rejoin his disciples in Galilee…

On the other hand, Matthew does not ritualistically avoid every change Luke made… resulting in dozens of minor agreements with Luke against Mark. Of particular, Matthew agrees with Luke’s assessment that Mark 11:11 is superfluous; like Luke he omits it and compresses the Triumphal Entry and the Cleansing of the Temple into the same day. However, these changes notwithstanding, in every important respect Matthew’s Gospel was written with the intent to supersede both Mark and Luke in the depth and diversity of their Jesus traditions.

(Evan Powell, The Myth of the Lost Gospel, pp. 93-94)

Matthew clearly contains much material that exists in Mark or Luke or the combination of the two. In using these two primary sources, he conflates them along with other materials into a more expanded and embellished Gospel. In the composition process, Matthew integrated fragments from both Mark and Luke, when creating his own super-narrative.

The key observation to be made is that Matthew is a text that conflates material of Mark with the material of Luke, and that this is an activity unique to Matthew. For example, Luke exhibits no similar array of text that have evidence of being composed of elements of Mark and Matthew. But if Luke had used Mark and Matthew, we should be able to detect a similar pattern that we see in Matthew. With respect to the Q theory, there is also a similar discrepancy in comparing the conflation characteristics of Matthean with respect to Luke, which does not exhibit conflation. The textural pattern of conflation in Matthew, and its comparative absence from Luke, is a strong indication of Matthean Posteriority. Let’s look at three examples of passages in Matthew exhibiting a high level of intertextual weaving of Mark and Luke together.

The Calling of the Twelve

- Mark 6:6b

- Luke 8:1

- Mark 6:34

- Luke 10:2

- Luke 9:1b

- Mark 3:14-19

- Luke 6:13-16

Let’s look at the parallels with Matt 9:35-38 more closely:

Mark 6:6 (NRSV)

6 And he was amazed at their unbelief. Then he went about among the villages teaching.

Luke 8:1 (NRSV)

1 Soon afterwards he went on through cities and villages, proclaiming and bringing the good news of the kingdom of God. The twelve were with him,

Mark 6:34 (NRSV)

34 As he went ashore, he saw a great crowd; and he had compassion for them, because they were like sheep without a shepherd; and he began to teach them many things.

Luke 10:2 (NRSV)

2 He said to them, “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few; therefore ask the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest

Matthew 9:35-38 (NRSV)

35 Then Jesus went about

all the cities and villages, teaching in their synagogues, and proclaiming the good news of the kingdom, and curing every disease and every sickness.

36 When he saw the crowds, he had compassion for them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd.

37 Then he said to his disciples, “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few; 38 therefore ask the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest.”

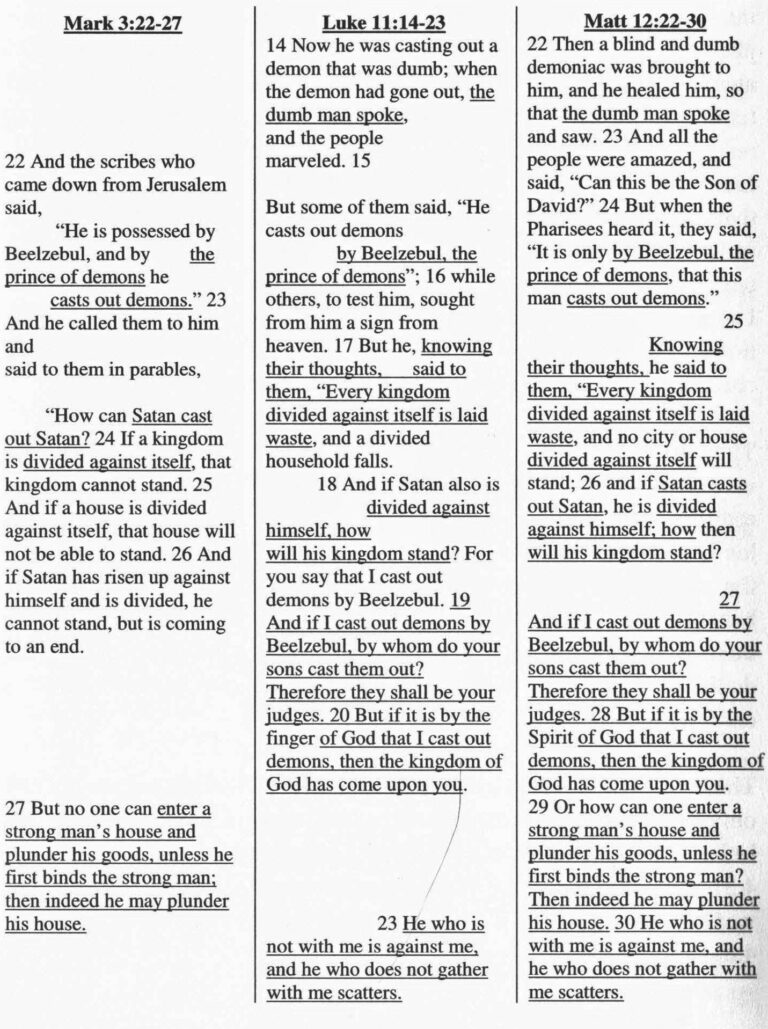

The Beelzebul Controversy

Matthew 18:1-22: Little ones, temptations, and forgiveness

Now let’s look at verses from Luke and Mark that correspond to Matthew 18:1-22. We see below that Matthew is the most polished and developed, implementing elements from both Luke and Mark. Matthew is not always as expansionist as Mark, but often greatly expands on Luke. Significant Matthean revisions and additions are highlighted in bold.

Mark 9:33-37 (ESV)

33 And they came to Capernaum. And when he was in the house he asked them, “What were you discussing on the way?” 34 But they kept silent, for on the way they had argued with one another about who was the greatest. 35 And he sat down and called the twelve. And he said to them, “If anyone would be first, he must be last of all and servant of all.” 36 And he took a child and put him in the midst of them, and taking him in his arms, he said to them, 37 “Whoever receives one such child in my name receives me, and whoever receives me, receives not me but him who sent me

Matthew 18:1-5 (ESV)

1 At that time the disciples came to Jesus, saying, “Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?” 2 And calling to him a child, he put him in the midst of them 3 and said, “Truly, I say to you, unless you turn and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. 4 Whoever humbles himself like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven. 5 “Whoever receives one such child in my name receives me,

Mark 9:42 (ESV) / Luke 17:2

42 “Whoever causes one of these little ones who believe in me to sin, it would be better for him if a great millstone were hung around his neck and he were thrown into the sea.

Matthew 18:6 (ESV)

6 but whoever causes one of these little ones who believe in me to sin, it would be better for him to have a great millstone fastened around his neck and to be drowned in the depth of the sea.

Luke 17:1 (ESV)

1 And he said to his disciples, “Temptations to sin are sure to come, but woe to the one through whom they come!

Matthew 18:7 (ESV)

7 “Woe to the world for temptations to sin! For it is necessary that temptations come, but woe to the one by whom the temptation comes!

Mark 9:43-48 (ESV)

43 And if your hand causes you to sin, cut it off. It is better for you to enter life crippled than with two hands to go to hell, to the unquenchable fire. 45 And if your foot causes you to sin, cut it off. It is better for you to enter life lame than with two feet to be thrown into hell. 47 And if your eye causes you to sin, tear it out. It is better for you to enter the kingdom of God with one eye than with two eyes to be thrown into hell, 48 ‘where their worm does not die and the fire is not quenched.’

Matthew 18:8-9 (ESV)

8 And if your hand or your foot causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away. It is better for you to enter life crippled or lame than with two hands or two feet to be thrown into the eternal fire. 9 And if your eye causes you to sin, tear it out and throw it away. It is better for you to enter life with one eye than with two eyes to be thrown into the hell of fire.

Luke 15:3-7 (ESV)

3 So he told them this parable: 4 “What man of you, having a hundred sheep, if he has lost one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the open country, and go after the one that is lost, until he finds it? 5 And when he has found it, he lays it on his shoulders, rejoicing. 6 And when he comes home, he calls together his friends and his neighbors, saying to them, ‘Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep that was lost.’ 7 Just so, I tell you, there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance.

Matthew 18:10-14 (ESV)

10 “See that you do not despise one of these little ones. For I tell you that in heaven their angels always see the face of my Father who is in heaven. 12 What do you think? If a man has a hundred sheep, and one of them has gone astray, does he not leave the ninety-nine on the mountains and go in search of the one that went astray? 13 And if he finds it, truly, I say to you, he rejoices over it more than over the ninety-nine that never went astray. 14 So it is not the will of my Father who is in heaven that one of these little ones should perish.

Luke 17:3 (ESV)

3 Pay attention to yourselves! If your brother sins, rebuke him, and if he repents, forgive him,

Matthew 18:15-20 (ESV)

15 “If your brother sins against you, go and tell him his fault, between you and him alone. If he listens to you, you have gained your brother. 16 But if he does not listen, take one or two others along with you, that every charge may be established by the evidence of two or three witnesses. 17 If he refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church. And if he refuses to listen even to the church, let him be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector. 18 Truly, I say to you, whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven. 19 Again I say to you, if two of you agree on earth about anything they ask, it will be done for them by my Father in heaven. 20 For where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I among them.”

Luke 17:4 (ESV)

4 and if he sins against you seven times in the day, and turns to you seven times, saying, ‘I repent,’ you must forgive him.”

Matthew 18:21-22 (ESV)

21 Then Peter came up and said to him, “Lord, how often will my brother sin against me, and I forgive him? As many as seven times?” 22 Jesus said to him, “I do not say to you seven times, but seventy-seven times.

Deeper textual evidence of Matthew’s knowledge of Luke

A principal argument for Matthean Posteriority is the numerous parallel passages in the Synoptic Gospel that contain evidence that the Gospel of Luke was known to the author of Matthew. Here are several examples of parallel passages that can be seen to provide evidence of Matthew’s knowledge and use of Luke.

As an analogy for his use of Luke, examining Matthew’s reordering of Marcan material

- Healing of the Paralytic and controversy about forgiving sins: Mark 2:1-12 vs. Mat 9:1-8

- The Call of Levi and Eating with Tax Collectors and sinners: Mark 2:13-17 vs. Matt 9:9-13

- The question about fasting: Mark 2:18-22 vs. Matt 9:14-17

- Plucking Grain on the Sabbath: Mark 2:23-28 vs. Matt 12:1-8

- Healing the man with the withered hand on the Sabbath, Mark 3:1-6 vs. Matt 12:9-14

- The Parables Discourse: Mark 4:1-34 vs. Matt 13:1-52

- The stilling of the storm: Mark 4:35-41 vs. Matt 8:23-27

- The Gerasene demoniac: Mark 5:1-20 vs. Matt 8:28-34

- Jarius’ Daughter and the woman with a hemorrhage: Mark 5:21-43 vs. Matt 9:18-26

- Mission Instructions: Mark 6:8-11 vs, Matt 10:5-42

As compared to the 1-10 sequence of stories of Mark, Matthew is in the order. 7-8-1-2-3-9-10-4-5-6. Matthew transposed stories into his desired teaching blocks. Other Matthean recontextualizations of Markan sayings include the following:

- Matthew deletes Mark’s periscope of the strange exorcist (Mark 9:38-41) except for the final saying that he places at the end of his Mission Discourse, right after another saying about rewards (Matt 10:41-42)

- Matthew takes Mark 11:24, found at the end of Mark’s Withered Fig Tree periscope, and puts it at the end of a section on prayer in the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 6:14-15)

- In addition to maintaining the original context of the saying, ‘But many who are first will be last and many who are last will be first,’ Matthew adds the saying to a second context at the end of the parable of the workers in the vineyard (Matt 20:16). He makes the parable an illustration of the saying, and the saying the moral of the parable.

- Matthew omits the saying on receiving the kingdom as a child (Mark 10:15/Luke 18:17) from the context of Jesus blessing the children but adds a similar saying to his community discourse (Matt 18:3)

- Matthew removes the description of the crowd as ‘sheep without a shepherd’ from the Markan context in the feeding of five thousand (mark 6:34) and uses it in the introduction to his mission discourse (Matt 9:36)

- Matthew puts the saying on hearing with one’s ears in a different context (Matt 13:43 vs. Mark 4:23, Matt 14:9 vs. Mark 4:9 vs. Luke 8:8)

- Matthew puts the saying on receiving or losing what one has in a different context than Mark (Matt 13:12 vs. Mark 4:25)

Matthew’s Conflation of Luke and Mark in Matthew 10:9-10

Luke as the source for Matt 6:24 featuring the word ‘Mamon’

Luke 16 features the use of the word ‘Mamon’ three times in Luke 16:9, 11, 13. This Aramaic loanword occurs once in Matthew 6:24. If one presumes that Matthew was written after Luke, it is plausible that Luke could have received the entirety of his ‘mammon’ passage (Luke 16:9-13) from a single source and Matthew would have known the Lukan passage. Matthew possibly decided he didn’t want to use the preceding parable of the unjust steward (Luke 16:1-8) but did want to include Luke 16:13 in his section on focusing on heavenly things rather than earthly in the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 6:19-33). Thus, Matthew chose to retain the Aramaic expression for one selected context, similar to how he sometimes used Mark.

Luke as the source for Matt 6:19-21 ‘Do not store up treasures on earth’

In the treasures in heaven passages of Matthew 6:19-21 and Luke 12:32-34, Matthew and Luke are fairly close in the second half of the periscope but distant in the first half. If Matthew relied on Luke, the similarity between the two passages is easily explained in terms of Matthew’s dependence on Luke. In composing Matthew 6:19-34, Matthew draws on material from Luke 11 and 16, but primarily from Luke 12:13-34, the section of Luke’s Gospel dealing with holding on to possessions versus trust in God. Matthew selectively uses this material in an arrangement that suits his purposes. Matthew probably decides not to use Luke’s Parable of the rich fool (Luke 12:16-21) because he wants to incorporate mostly direct teachings in the Sermon on the Mount rather than extend parables. However, Matthew does see it useful to connect elements of Luke 12:21, the warning that those who store up for themselves are not rich toward God, and Luke 12:33, ‘unfailing treasure in heaven’ together in Matthew 6:19-21 while omitting Luke’s injunction, ‘Sell your possessions and give alms.’ Perhaps the implication of Luke renouncing earthly possessions was too radical for Matthew.

Luke as the basis for Mathew 23:37 on Jerusalem

Luke 10:4-6 as a precursor to Matthew 10:11-13, Travel Instructions

There are a few interesting differences between Matt 10:1-13 and Luke 10:4-6. In Matt 10:11-13 Matthew omits Luke’s command, ‘Do not greet anyone on the road’, but he appears to have read it since he immediately uses Luke’s verb to write, “When you go into the house greet it,” in place of Luke’s more Semitic, “say, Peace to this house.” It is also very likely that Matthew read Luke’s wording “Peace to this house,” since in Matt 10:13 he writes “let your peace come upon it,” in close arrangement with “your peace will rest upon it” in Luke 10:6. It is highly likely that Luke’s wording is more primitive than Matthew’s here. Taking a view of Matthean Posteriority in this passage is more logical. Otherwise, one would have to presume Luke decided not to use Matthew’s use of ‘greet’ and ‘worthy’ in the instructions about lodging and, in response to Matthew’s phrase “let your peace come upon it,” to have come up with the Semitic expressions “peace to this house” and “son of peace” with which to replace them. Furthermore, it also appears that Matthew was influenced by Luke 10:7 “laborer deserves his wages” in Matt 10:10 “laborer deserves his food.”

Luke as the influence behind Matthew 9:32-35 and 10:25, Beelzebul

Luke as a precursor to Matthew 12:22-24, other Beelzebul references

Lukan influence on Matthew 12:11, healing on the Sabbath

Luke has two stories involving controversy over healing on the Sabbath of Luke 13:10-17 and Luke 14:1-5 which both feature a defense of Jesus’ actions by giving an analogy of what people would normally do for their animals on the Sabbath. There is also a triple tradition pericope about the Man with the withered hand of Matt 12:9-14, Mark 3:1-6, and Luke 6:6-11 in which only Matt 12:11 makes reference to what people would do for their animals on the Sabbath. Matthew took his cue from the other Luke passages of Luke 13:15 and Luke 14:5 on using the argument of helping an animal. Matthew chose not to follow Luke in multiplying the stories of healing on the Sabbath but decided in the story of in Matt 12:9-14 to take Luke’s animal-in-a-pit analogy and insert it into what is for the most part the Markan version of the story Mark 3:1-6. Matt 12:11 is a redactional addition influenced by Luke.

Luke 16:14-17 as the catalyst for Matthew 5:17-20, Sermon on the Mount

Another clue that Matthew read Luke 16 is Matthew’s insertion of the remark of the necessity of having a righteousness that exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees (Matt 5:20). It is odd that Matthew would mention this at this point, since in Matthew’s narrative, Jesus had not yet been interacting with scribes and Pharisees. However, Matthew knows Luke’s Gospel and is familiar with Luke 16:14-15 of Jesus’ interaction with Pharisees being the immediate context of Luke 16:16-17. Thus, the presence of criticism of the Pharisees in both Matt 5:20 and Luke 16:14-15, together with Matthew’s attempt to clarify the ambiguity of Luke 16:16-17 regarding the Law, is an indication that Matthew incorporated Luke 16:17 and also crafted the sermon in a way to be responsive to the original Lukan context.

Later interpolations of Matthew of an unambiguous Judaizing quality

Matthew features explicit sayings regarding keeping commandments and judgment that are not seen in Luke. These sayings provide extra detail of a Judaizing quality and are of a non-ambiguous nature (Jesus is quoted as speaking plainly and directly). It doesn’t make sense if Luke is writing with Matthew in view, and that these are actually the words of Jesus, that he would omit such verses. The explanation of why Luke lacks these sayings is that Luke is the earliest of the three Synoptics and that the additional expressly formulated passages are interpolations developed and added by the author of Matthew and are of another later tradition associated with a Jewish-Christian Torah-observing sect. An example of such passages are as follows:

- Matthew 5:19-20—” Therefore whoever relaxes one of the least of these commandments and teaches others to do the same will be called least in the kingdom of heaven, but whoever does them and teaches them will be called great in the kingdom of heaven. For I tell you, unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.”

- Matthew 5:21- “Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but the one who does the will of my Father who is in heaven… Many… I will declare to them, ‘I never knew you; depart from me, you workers of lawlessness.’”

- Matthew 13:36-43— “The Son of Man will gather out of his kingdom all causes of sin and all law-breakers, and throw them into the fiery furnace”

- Matthew 16:26-27—” The son of Man… will repay each person according to what he has done.”

- Matthew 19:17— ”If you would enter life, keep the commandments”

- Matthew 23:2-3— “The scribes and the Pharisees… so do and observe whatever they tell you”

- Matthew 23:23—“The weightier matters of the law… these things you ought to have done, without neglecting the others”

- Matthew 25:31-46— ”He will say to those on his left, ‘Depart from me, you cursed into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels… and these will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.”

Conclusions

- The theory of Luke’s use of Matthew is highly problematic. The theory of Matthews’ use of Luke is a better solution.

- Matthew expands on Luke. Although Luke is longer than Matthew in length, Matthew developed a more refined and expansive interpretation of Jesus’ traditions, including the Lord’s Prayer, Beatitudes, and Great Commission. The statistical distribution of materials between Luke and Matthew, as well as the qualitative enhancements of Matthew over Luke, are consistent with the proposition that Matthew was composed some time after Luke.

- Numerous examples of Matthean revision to Luke including clarifications and embellishments are further evidence of Matthean Posteriority. The existence of this unique explanatory material in Matthew constitutes more evidence that Matthew was the last of the Synoptic Gospels to have been composed.

- Examples given of Matthean conflation of Mark and Luke, clearly indicate that the other combined these sources. This is an activity unique to Matthew. Luke exhibits no similar array of text that have evidence of being composed of elements of Mark and Matthew. But if Luke had used Mark and Matthew, we should be able to detect a similar pattern that we see in Matthew.

- Numerous examples are given as deeper textual evidence of Matthew’s knowledge of Luke. These examples indicate Matthew’s specific knowledge of Lukan content, although using Luke as a secondary reference to Mark.

- Later interpolations aligned with the author’s theological aims are identified that are of an unambiguous Judaizing quality. The additional expressly formulated passages are clearly interpolations, developed and added by the author of Matthew, are of another later tradition associated with a Jewish-Christian Torah-observing sect.

All the above demonstrates that Matthew was written last of the synoptic Gospels.